The Inaugural McKay Distinguished Lecture, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan. October 3 2025

The Tensions Between Medicine and Healthcare: Reflections on Medical Education and AI

By Gerald Chan

I’d like to begin by framing the problem. In calling attention to tensions between medicine and healthcare, I am indeed saying that the two are distinct even though they are intimately related and share the same intent of bringing health to people. My thinking is that the tensions between the practice of medicine and the management of healthcare have come to a head that they should be called out and examined in the hopes that we can find pathways forward that are workable for all stakeholders.

Medicine is the art and science of healing. People who experience physical ailments come to the physician in search of understanding of what ails them and in search of remediation. The work of a physician is therefore of two parts. The first is to map the patient’s symptomatology onto a system of knowledge, what is known at the time about how the human body functions and how it goes wrong. This mapping informs the physician’s strategy for remediation. Hence, the work of the physician is one of diagnostics and therapeutics. By therapeutics, I mean not only pharmacological agents which are commonly called therapeutics, but also any intervention such as surgery, procedures, advice on lifestyle, etc.

As a profession, medicine is fundamental to human society. Together with theology and law, they address the primal human needs for physical health, for meaning and for harmonious living with one’s fellow men. It is no wonder that these three professions were the first to be formalized into professional schools as universities came into being in medieval times. For the medical profession, there is a humanistic dimension to the ministration of its services that goes beyond the relationship between the purveyor and the purchaser of any goods and services in a purely commercial transaction. The doctor patient relationship is indeed one that is regarded as having an element of moral sanctity.

Because medicine has the power of alleviating human suffering, it has a particular appeal to the altruism of people who choose the profession. In talking to pre-med undergraduates nowadays, I detect the humanitarian impulse much more than pecuniary aspirations in those who set their sights on medicine. The interest in science is the other major driver.

Healthcare, on the other hand, is about the conglomeration of resources into an organized system in which medicine is practiced. It is the infrastructure by which the healing art is delivered to the patients. When medicine was primitive, there was no need for healthcare systems. The physician was the sole agent who, as a solo practitioner, could deliver all that medicine had to offer. I think of Albert Schweitzer practicing medicine single-handedly in Africa. He treated all manners of sickness as well as did surgery, sometimes with his wife acting as the anesthetist.

With modern medicine being highly developed today, no physician can single-handedly do everything that medicine has to offer, nor does the patient necessarily know where among the branches of medicine should he go to seek help. He needs a system as intermediation between him and the physicians who will ultimately remediate his health problem. That system is what we call healthcare, a system that is now both massive and highly complex.

Consider the physical facilities of healthcare which stretch from community health clinics to academic medical centers. A modern academic medical center is a colossal complex of buildings. For example, the Mayo Clinic campus in Rochester, Minnesota has over ten million square feet of built space filled with high-tech equipments. If we use the very conservative rule of thumb that it takes $1500 to build and equip one square foot of a hospital, ten million square feet would translate to a cost of $15 billion. Healthcare is a capital intensive business.

Then there is the personnel side of healthcare. Physicians are now divided into many specialties. Besides the physicians, there is a plethora of other professionals such as nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, various therapists, technicians as well as other paraprofessionals and support staff. The largest employer in the state of Massachusetts is Mass General Brigham with over eighty-two thousand employees. To put that number in perspective, MGB has half the number of employees as what Apple Inc has worldwide and Apple is the third largest company in the world with a market capitalization of over three trillion dollars. Today, in 38 of the 50 states in America, there are more people working in healthcare than in any other industry.

Then there is the financial aspect of healthcare which is complex and convoluted. In the U.S., payment for healthcare comes primarily not from the patients, but from third party payers which include insurance companies, employers, and the government. The largest payer for healthcare in America is the federal government. About a quarter of its $7 trillion dollar annual outlay goes to providing healthcare for Americans. The payment models in healthcare are also variable and complex; there are straight-up fee-for-service payment models, and there are outcome based, or value based payment models. The latter usually involves some party in the food chain bearing financial risk, and reaping financial reward, for the health outcomes.

Because the Federal Government, through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), pays for about 40% of all the healthcare expenditure in this country, health systems have the problem of extreme concentration of customers and with that, the surrender of all pricing power over a large proportion of their patients. Before DRGs were introduced in 1983, CMS used to reimburse under a cost plus scheme. Not any more. Today, in some instances, the cost to the health system for a service it provides exceeds the amount reimbursed by CMS. To offset such impact on margin, the health system has to rely on more lucrative commercial business to balance the books.

The pricing of services offered by different medical specialties also varies greatly. Surgery is high margin whereas psychiatry and pediatrics are low margin. Primary care has negative margins, but health systems still build their network of primary care doctors as a funnel to refer patients who need higher acuity care which brings higher margin work. Primary care is a loss leader. For the same reason, standalone solo or small primary care practices are disappearing. They either sell out to health systems which can smooth out the high and low margin businesses, or to private equity players who pursue a consolidation play. Either way, the doctors become employees of large organizations. The family doctor in solo practice looking after multiple generations of patients from the same family is now an historical artifact.

Then there is the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act passed by Congress in 1986 which prohibits hospitals from refusing care to any patient that shows up at the emergency room regardless of his ability to pay for the care he needs. If the patient is indigent, the hospital may end up eating the cost for his care. It is noble for charitable intents to be legislated into law, but someone still has to shoulder the financial burden of that care.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic laid bare how vulnerable are the finances of health systems to large-scale shocks. I know of one health system which weathered the pandemic by spending down its endowment from one billion to half a billion dollars. At the peak of the pandemic, one medical center in Boston spent 50 million dollars per month on traveling nurses as its regular nursing staff was hit by mass resignations. I know of another major health system which, after the pandemic, was operating with a cash reserve sufficient to cover only one and a half days of its operation. Fortunately, that system was the teaching hospital of a university and was able to look to the university’s endowment for support.

As a business, healthcare is a low margin, high volume business. In a good year, a health system makes a positive margin in the low single digits, about the same as supermarkets. From an investment standpoint, it is hard to think of an industry as unattractive as the healthcare industry — capital intensive, labor intensive, operationally intensive, low margin, no pricing power, highly regulated by multiple agencies, required by law to serve customers who cannot pay, and subject to catastrophic shocks. Cynically, healthcare organizations are non-profit not because of their charitable intent (that is distant history), but because without tax exemption, this industry cannot attract capital in the open market. Looking through this lens, it becomes more understandable why health systems are constantly pressuring their physicians to produce more. Such pressure is not because of sinister avarice on the part of management. In a low margin high volume business, squeezing out more efficiency is a matter of survival.

What is happening in our times is that medicine is being industrialized. Much as the Industrial Revolution some two hundred years ago made manufactured goods broadly available to people, the industrialization of healthcare is what it takes for medicine to become broadly available to people. Industrialization transforms luxury goods into commodity.”

Indeed, throughout most of human history, access to healthcare was a luxury item. At best, there were charities to bridge the affordability gap for the indigent. The hardships of World Ward II catalyzed a shift in the social attitude towards healthcare. Instead of healthcare being a luxury item paid for by the consumer, the new consensus was for the state to pay for healthcare. In a moment of exuberance in 1948, the world came together at the United Nations and made a declaration that was said to be universal. Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care…” By this one declaration, the conception of healthcare was transformed from a human need to a human right and by extension, an entitlement. In the hierarchy of rights, healthcare was elevated to be on par with food, clothing and housing.

The evolution of healthcare in the second half of the twentieth century largely followed the tenet of the Universal Declaration. In Western European countries, healthcare became socialized as exemplified by the National Health Service of the United Kingdom which today employs 1.6 million people. Notwithstanding America’s aversion for socialism, here we are in 2025 at the sixtieth anniversary of the legislation that created Medicare and Medicaid. In six decades, the Federal budget devoted to healthcare ballooned from zero to 22% of this year’s budget. Healthcare is the largest expenditure of the Federal Government, exceeding that for social security and national defense. Today, the attitude of the American people towards healthcare is not whether government should pay for it, but how extensive should the coverage be. For example, ten states opposed Medicaid Expansion introduced by Obamacare whereas forty states are in favor. The divergence is only a matter of degree. Earlier this week, the government shutdown was brought about by precisely this difference between the two political parties on how much government should pay for healthcare.

Any attempt to rein in government expenditure in healthcare will not be easy because on the demand side, the aging demographics and the shifting of the disease burden from acute to chronic diseases make for ever higher demand for healthcare. The highest consumption of healthcare occurs in the gap between health span and life span. From 2000 to 2019, this gap in America increased from 10.9 to 12.4 years. On the supply side, scientific and technological progress has endowed medicine with ever more diagnostic and therapeutic options. People with cancer used to die after exhausting one or two lines of therapy. Today, there are third, fourth, and fifth line therapies, and they all get progressively more expensive. In a clinical trial of one of my portfolio companies, we recently treated a multiple myeloma patient who had failed six lines of prior therapies including a bispecific antibody which the FDA approved only for patients who had failed at least four lines of prior therapy. The GLP-1 drugs used for obesity is another example of how innovation in medicine can come nigh to bankrupting healthcare payers. The explosion in healthcare cost is a perfect storm of inelastic demand meeting explosive supply.

The financial reality of healthcare is forcing us as a society to come to terms with how far can we push the convergence between what medicine can do for a patient and what healthcare can afford to do for that patient. The critical question here is who is to make that determination for each patient. It used to be the doctor. Today, the payers have wrested much of that decision power away from the doctors. We now have doctors spending ever more time advocating for patients to the payers even as the probability of success is ever diminishing. From 2016 to 2023, prescription drug denials by private insurers went up by 25%. Public resentment of such insurance denials found expression in the tragic shooting of the CEO of UnitedHealthcare last year.

For physicians today, there is a growing sense of loss of autonomy. This feeling is strikingly similar to the feeling of workers in the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century. Karl Marx gave new meaning to the word alienation in describing how factory workers of his time felt a loss of control over their work and estrangement from their work product; work became externally directed and felt forced rather than being self-directed and meaningful. Eventually, the sense of alienation eats away at the workers’ sense of fulfillment derived from work, their creativity and even their very humanity. Today, we call the feeling experienced by doctors burnout.

It would be simplistic to think that doctors’ burnout results only from their being overworked and underpaid. Rather, it is doctors being told how they should practice medicine such as how much time a doctor can spend with a patient, or how much OR time is allocated to a surgery. Strict control of how much time a worker can spend on each task was a key element in the industrialization of manufacturing. It came to be known as Taylorism in early twentieth century factories in America after the practice of strict time control advocated by Frederick Winslow Taylor. For healthcare managers, increasing throughput or minimizing staffing are logical steps to improve efficiency and productivity. For the physicians, it is a matter of whether they are allowed to care for their patients as their professional judgement dictates, and ultimately, whether they feel their commitment to do what is best for their patients is being compromised.

Whether one calls it loss of autonomy or moral injury, it is a rude awakening for doctors to discover that they are now employees of massive healthcare organizations whose commercial realism is all too pervasive in their work life. Today, two thirds of physicians in America are employees of either corporate entities or hospital systems. Should we be surprised that doctors are calling for unionization? That was exactly what happened with factory workers in nineteenth century Industrial Revolution. Who would have thought that the Massachusetts General Hospital, one of the high temples of medicine, would become a union shop? For the old timers who know what the Mass General stood for in medicine, that would have been as unthinkable as if someone were to propose today that the clergy of the Anglican Church be unionized.

In the longer term, we should be concerned that the lack of fulfillment in the practice of medicine will lead to medicine losing its competitiveness for attracting top talents among the young people. In one survey of 7500 physicians, 63% do not wish their children to go into medicine. Not surprisingly, the physicians who practice in low paying specialties are less likely to recommend their children to follow them, and vice versa. For medical school graduates, practicing medicine is no longer the only career path open to them. McKinsey or Wall Street firms will dangle salaries three to four times that of a resident’s salary to fresh medical school graduates. For the medical students aspiring for greater impact from their work or for those interested in advancing science, there is a quiet revolution in their thinking that practicing medicine may not be the most productive path forward. A friend of mine and I host a dinner club in Boston for a group of non-practicing Harvard Medical School graduates who have ventured into the startup world.

The American Association of Medical Colleges projects a shortage of 86,000 physicians in America by the year 2036. The current pipeline for future physicians is evidently not working. If we are to have an adequate healthcare system in the future, I think we must begin by rethinking medical education with an open mind.

Young people may still have the time to spend eight years in school, but it is a severe financial stress to be in school for so long to be followed by four more years of low paying residency. Everywhere in the world, young people go directly into medical school upon graduation from secondary school with the exception of America and Canada. The reason is the Flexner Report of 1910. At that time, the quality of medical education was shoddy and spotty. Flexner called for students to be first trained in science before they enter training in medicine. It seemed like a perfectly reasonable prescription for the time, but it was actually somewhat spurious.

The real reason for the poor quality of medical education at Flexner’s time was the primitive state of medicine itself. By the early twentieth century, the science of chemistry and physics had flourished and was much more developed than the science of medicine. The medical essayist Lewis Thomas who was President of Memorial Sloan Kettering rightly called medicine the youngest science. As late as when Thomas was a student at Harvard Medical School in the 1930s, he described his curriculum as “to teach the recognition of disease entities, their classification, their signs, symptoms, and laboratory manifestations, and how to make an accurate diagnosis. The treatment of disease was the minor part of the curriculum, almost left out altogether.” He wrote of his experience as a third and fourth year medical student in clinical rotation, “It gradually dawned on us that we didn’t know much that was really useful, that we could do nothing to change the course of the great majority of diseases we were so busy analyzing, that medicine, for all its façade as a learned profession, was in real life a profoundly ignorant occupation.” For Thomas, medicine amounted to diagnostics plus supportive care. He called it Osler’s therapeutic nihilism which, in retrospect, was real progress from the therapeutic quackery of Flexner’s time. Medicine evolved from doing harm to doing no harm.

Flexner’s call for doctors to be first trained in science should be given credit for laying the foundation for the subsequent development of medical science. From the advent of antibiotics to now, we have had a century of golden age of therapeutics which saw the development of amazing small molecule drugs as well as biologics made possible by recombinant DNA technology.

For medical education, what we have today is Flexner gone overboard. While Flexner called for pre-medical training in science, he did not mandate a four year undergraduate degree as a prerequisite for applying to medical school. In 1949, only 4 medical schools in America required a bachelor’s degree for admission, 58 schools required three years and 7 schools required only two years of undergraduate studies. University of Michigan required three. When I hear about pre-med undergraduates struggling with organic chemistry, I wonder how often in the routine practice of medicine does the knowledge of organic chemistry make a difference. I know of many highly competent clinicians including some to whom I have committed the care of myself and my loved ones who have hardly a working knowledge of the basic science that is stock in trade used everyday in the business of drug development.

The central question is whether we are educating for medicine as a practice or medicine as a science. The program of four years of pre-med and four years of medical school is more suited for training physician scientists rather than training practicing physicians. We all have interacted with physicians trained in countries like UK or Australia where medical school is 5 to 6 years from high school graduation. They are perfectly competent clinicians. In these countries, the duration of pre-med and medical school is shorter but the clinical training is longer than what is typical in the American system. Those who want to go into academic medicine would go on to do a PhD degree. This seems more rational for resource allocation as to be fit for purpose, economical and efficient.

I applaud the medical school curriculum here in Michigan of only one year of pre-clinical studies and one year of clinical rotation. It is totally aligned with the structural changes pioneered by NYU in making medical school three years instead of four. Having graduated seven cohorts of the three-year program, NYU published their finding last year that by various metrics of professional competence, the graduates from the three-year program do just as well as the graduates from the four-year program. Abbreviating medical school did not lead to degradation of quality of graduates.

When it comes to the sheer number of doctors we turn out, the conservatism of medical schools has held back the expansion of capacity. Two trends have arisen to make up this lack. One is the growth of osteopathic medical schools whose enrollment has grown in the last decade by 70%, more than three times the rate of growth of allopathic medical schools. Today, almost 30% of medical students are enrolled in osteopathic medical schools. Graduates of osteopathic medical schools are more likely to practice in primary care and in rural areas of America where healthcare is least available. In 2024, researchers from UCLA published a review of 2 million surgical procedures and found no statistically significant difference in 30 day mortality, hospital readmission or length of hospital stay whether the surgery was done by a surgeon with a MD or a DO qualification.

The other trend is that health systems are starting their own medical schools. Kaiser Permanente and Geisinger in Pennsylvania are prime examples. The Virtua health system in New Jersey partnered with Rowan University to stand up an osteopathic medical school. The Ochsner system in Louisiana partnered with Xavier University, a historically black college to build a new medical school. The BayCare health system in Tampa, Florida just announced an affiliation with the Feinberg School of Medicine of Northwestern University. Building medical schools de novo from the base of a health system nullifies the common excuse that there is not enough capacity for clinical training in the teaching hospitals. The quality metrics of a system like BayCare in Tampa is every bit on par with that of academic medical centers. There is no reason why they cannot provide adequate training for medical students and residents.

Many of the new medical schools were formed with the explicit intention of training primary care physicians. On the surface, it may seem like the issue is the shortage of primary care physicians, but something more fundamental is going on as exemplified by the Alice Walton School of Medicine in Arkansas. The school is designed for medical students to be inducted into the value based model of care. While value based care is ostensibly a financial model, it was designed for better long-term health outcomes at the population level. The Alice Walton School of Medicine states explicitly its goal of training doctors who prioritize keeping patients healthy and for them to understand “the financial incentives in the system and what they should be so we can move towards value-based payments.” In essence, it is a shift away from a fee-for-service, transactional style of medicine to doctors following patients longitudinally for their care. The country whose healthcare system gets this right is Israel where primary care doctors are paid as well as the specialists.

Harking back to my original thesis of the tensions between medicine and healthcare, it is advisable that we build in more stratification in whether we are training doctors to advance the frontier of medicine or whether we are training practitioners to carry out the work of healthcare. Is it not time that in addition to celebrating heroic medicine, we also become more intentional in increasing the capacity of healthcare, and better yet, work to keep people healthy and reduce the demand for healthcare? A clearer definition of the objectives and pathways will align the expectations of the prospective medical students with the needs of society.

Finally, it would be incomplete to talk about the future of healthcare without talking about AI. When the demand for healthcare is non-linear, no linear solution such as building more medical schools will be able to meet the need. A linear supply curve can never catch up to a non-linear demand curve. The only solution that is infinitely scalable is AI.

I will illustrate the potentialities of AI in healthcare by describing four approaches I have used in building digital health companies in the last few years. The first, not surprisingly, is to use data to train the AI models to recognize patterns for the purpose of diagnosis.

For diagnosis of patients on the autism spectrum, the company Cognoa (run by a Michigan alum who is a pediatric neurologist) developed a FDA approved software to score a subject’s behavior in order to determine whether the child is on the autism spectrum. This software has a 95% positive predictive value and a 97% negative predictive value with 22% of the cases as indeterminate, these being likely cases more complex than just the autism spectrum. The parents only need to upload two videos of the child in some activity and answer a brief questionnaire. Instead of the current situation of months of waiting time for a child to be assessed by a neuropsychologist and thereby missing the time window of neuroplasticity where intervention can be most effective, children can now be assessed with no waiting time.

Linus Health is a five-year old company that has developed a 7-minute assessment of cognition that is approved by the FDA. Done on an iPad, the assessment is sensitive enough to identify cognitive impairment in patients who are considered clinically asymptomatic. In one study, a group of patients who were deemed cognitively normal by the MMSE test, but upon further full neuropsych workup were found to be cognitively impaired, the 7-minute test of Linus Health correctly identified 84% of them as cognitively impaired. Furthermore, the output of the Linus test can distinguish the pathology underlying the impairment as Alzheimer’s, frontal temporal, vascular or Lewy body dementia. In addition to being deployed by 14 health systems, Linus Health has contracted with Optum for a nationwide rollout of the Linus test to screen four million people over the age of 65 for cognitive impairment.

The second approach is to use AI to mimic the skills of a specialist and make it available to the primary care physician at the point of care. Last year, my colleagues and I founded the company Dermatic which has built an AI engine that enables the primary care physician to resolve most cases of skin conditions without having to refer the patient to a dermatologist. For the patients, this technology does away with waiting time to see a dermatologist. For the dermatologists, this reduces the superfluous referrals of normal or low acuity cases. The template is now being replicated for cardiopulmonary and GI disorders. In the future, the tech-enabled primary care physicians can do a lot more at the point of care without referral to specialists.

The third approach is to use AI for remote patient care and remote patient monitoring. Companies in the Morningside portfolio have used such technology to reduce pediatric emergency room usage by 43%, reduce 30-day hospital readmission rate of congestive heart failure patients from the CMS average of 24% to 3%, or reduce 30-day readmission rate of COPD patients by 50%. These are data from large-scale, real life deployments and not from controlled clinical trials.

The fourth approach is to use AI agents to increase patient engagement. This is most powerful in coaching patients with chronic conditions to adopt healthy lifestyles. For improving engagement with patients so that they take more agency for their own health, the company League is working with thirteen health plans such as Cigna and Highmark to prompt patients to take actions for managing their own health. Of 100 million health recommendations sent to patients, such as prompting the patient to measure his blood pressure, or to make an appointment with his healthcare provider, 60% of the recommendations were acted on by the patient and completed. For health plans that have rolled out the League portal for their members, the number of preventive health visits increased by 4X.

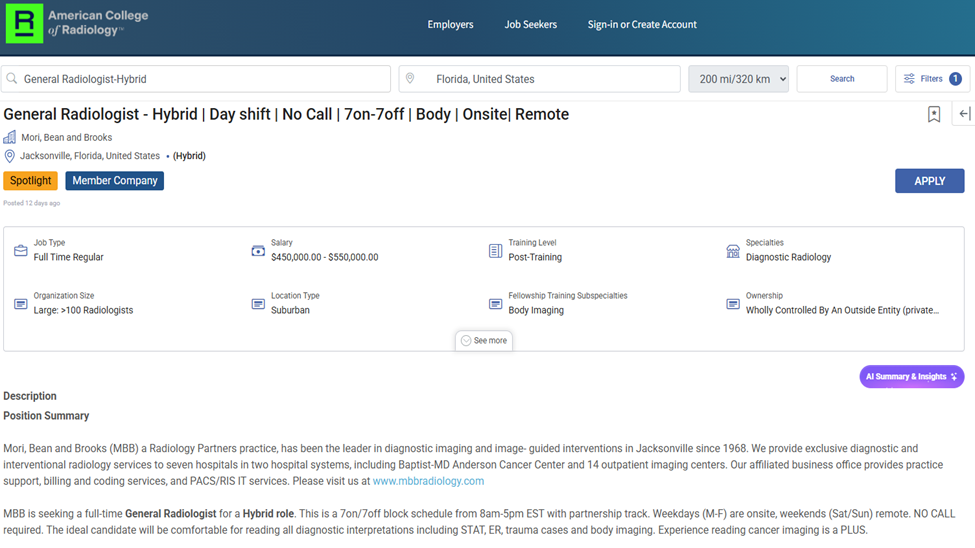

Seeing that there are many practicing physicians in the audience, I must not sign off without answering this burning question. Will AI destroy jobs of physicians? My answer is a definite no. My analogy is that while airplanes can fly autonomously, I don’t think we will ever have an empty cockpit in a passenger airplane. If compensation was an indication of supply and demand and what is to come, consider this. It is commonly thought that the jobs of radiologists are most at risk for disruption by AI. Were that to be the case, we would expect the compensation for radiologists to decline. The website of the American College of Radiology has hourly new postings for vacancies in radiology jobs. Here is one.

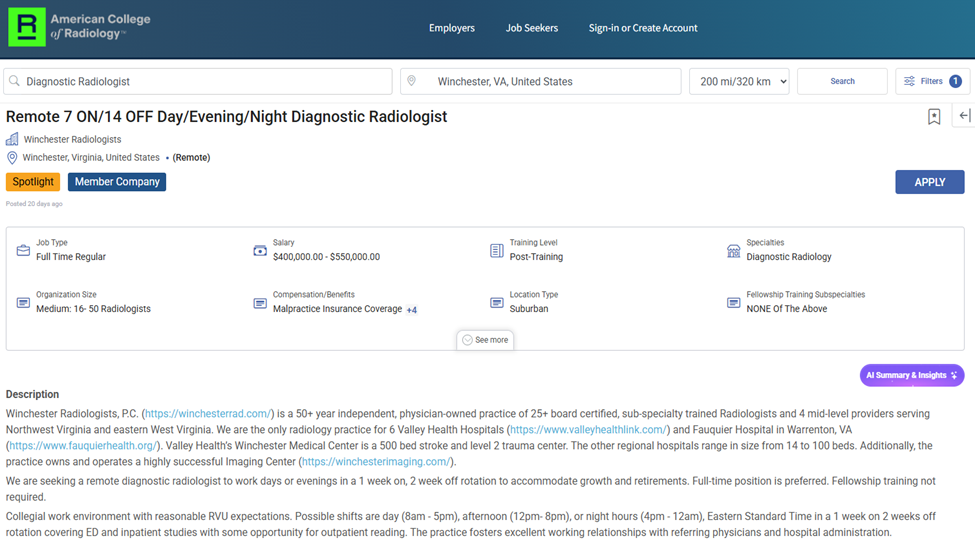

If you think working 7 days on and 7 days off is not good enough, here is one that offers 14 days off for 7 days of work. This works out to 234 off days in a year.

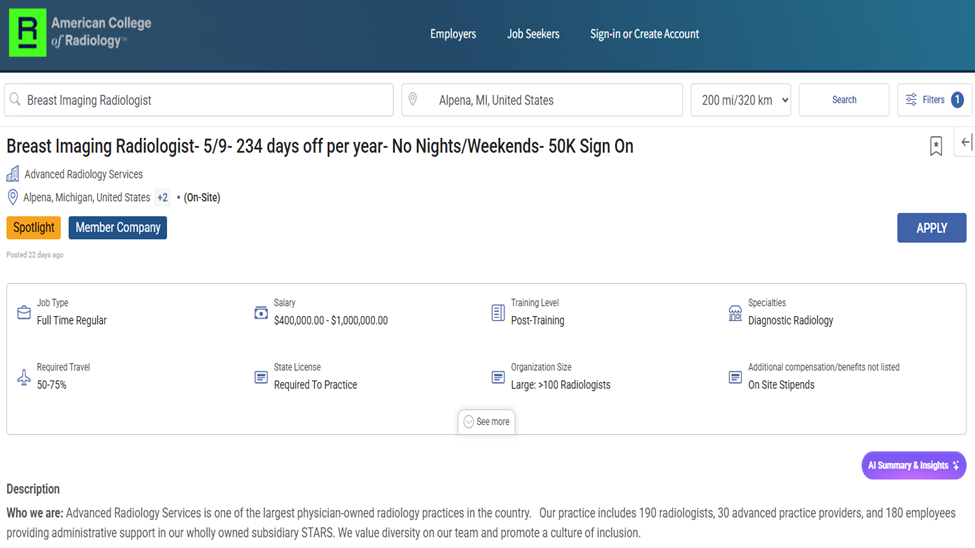

And if that is still not good enough, here is one with a $50K sign-on bonus thrown in.

On this happy note, let me assure you that AI will not displace physicians, but AI will make physicians more productive and allow physicians to better care for patients. AI has the potential of bringing to the masses what medicine can do in ways that healthcare can afford, thus arresting or better yet, reversing the opposing trends in recent years of medicine becoming ever more powerful while healthcare becomes ever more inaccessible. This, I hope, will finally bring some resolution to the tensions between medicine and healthcare.